Something We All Work On

Finding Slack's go-to-market. We didn’t sell saddles. But we needed to sell Slack. Getting over the Suck Hump.

Okay! We had an answer with some proof to back it up to our first key question: What is Slack?

Now we needed to build a plan to market and promote Slack. Oh, and it couldn’t really feel much like marketing and promotion. We felt pretty allergic to marketing and promotion in its traditional practices. We felt pretty sure our customers did too.

But we needed to do it. We needed to tell people about Slack or we’d end up another failed company no one knew. So how could we market Slack without it feeling like the ick of marketing?

From that question came some core ideas we talked about internally and that Stewart published as an essay called We Don’t Sell Saddles Here.

Just as much as our job is to build something genuinely useful, something which really does make people’s working lives simpler, more pleasant and more productive, our job is also to understand what people think they want and then translate the value of Slack into their terms.

A good part of that is “just marketing,” but even the best slogans, ads, landing pages, PR campaigns, etc., will fall down if they are not supported by the experience people have when they hit our site, when they sign up for an account, when they first begin using the product and when they start using it day in, day out.

Therefore, “understanding what people think they want and then translating the value of Slack into their terms” is something we all work on. It is the sum of the exercise of all our crafts. We do it with copy accompanying signup forms, with fast-loading pages, with good welcome emails, with comprehensive and accurate search, with purposeful loading screens, and with thoughtfully implemented and well-functioning features of all kinds.

The whole thing stands up very well to the 12 years since its creation and I’d say is well worth reading in full if you want to learn about what was happening at Slack at the time and in the years that followed.

(As a sidenote, even the essay itself, shared first with the Tiny Speck team internally and then shared publicly with the world just prior to our paid product launch, acted in the strategy it espoused. It was marketing and brought more people to Slack.)

So let’s dig a bit deeper on the next key question we faced: how to market Slack? How to get beyond features and functions to help people see the incredible promise available to them if they used Slack? And how to work backwards in our customers’ experience to get them to the experience we knew could be transformative?

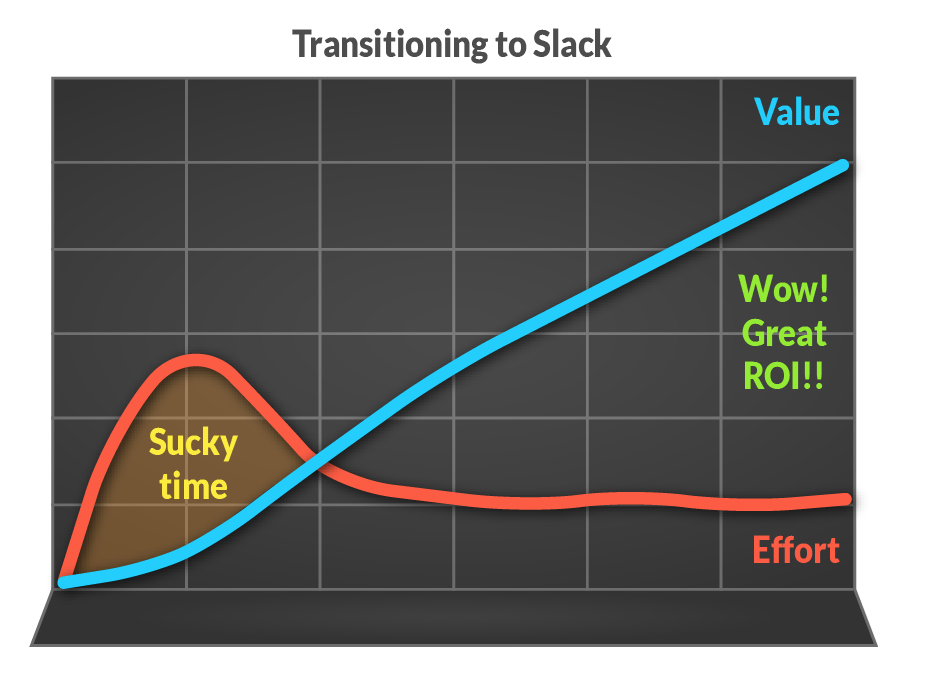

To start, we had a graph that told us one thing and led us to the most important thing to work on.

Getting over the Suck Hump

The graph I’m talking about arose from a conversation Stewart and I had about how to get people to change, which was hard. And change against a collective action problem, which was even harder because they needed to change and they needed their teammates to change.

We’ve talked about this two-stage problem before.

So we had both a cold start problem (why would I use this if there’s nothing in here to use it with?) and the multi-user problem (who would I use this with if the people I communicate with aren’t on it?). There was a huge amount of friction to get people to begin using Slack and to get their teams using it.

From that understanding, I drew a rough series of lines on a whiteboard trying to represent the experience of most folks transitioning to Slack. Stewart made the drawing digital.

The drawing illustrated our understanding of our go-to-market challenge. We had to get people to believe in the incredible promise available to them with Slack because they had to get over the Suck Hump to get to the Wow! Great ROI!! promised land.

Right, so. How?

That was the question I believe everyone at Slack felt a responsibility to answer in their own part of the organization once they read We Don’t Sell Saddles Here. It had become the most important thing to work on. We needed to launch sometime. We needed to figure out how to get people over The Suck Hump as well as possible for that launch.

For me in marketing, here are a few ways that getting over the Suck Hump showed up and became part of our larger strategy.

Finding an enemy – Email, yes, but more too. Email as the representation of what people found frustrating in their work. Email as stodginess, as control, as stalling, as information hoarding from those unwilling to embrace change. Email as the enemy everyone had to bear and defeat every day to actually get their work done.

Making change inevitable – Email is a remnant from an analog world. It’s in the name, an abbreviation of electronic mail. It has a To:, a From:, a Subject, a Signature. It’s paper memos in digital form that travel from person to person, and confined to the people who are explicitly defined as needing to see it. It’s closed to everyone else by default. Moving to a digitally native communication system where information is open for everyone by default, instead of being locked into the inbox of someone, is inevitable.

Slack as wedge for change – What do you want to change in your work? Slowness of decision making? Slack accelerates that. Closed levers of power based on information hoarding? Slack fixes that. Opacity of responsibility and accountability? Just put a Slack on that. These were the prime ailing symptoms that required change to fix and Slack was the general purpose pain killer.

Alignment with customers – Slack could only succeed if our customers succeeded. We needed our customers to succeed. Use Slack and find it valuable? Great, only then would you keep using it. Like Slack and find it improves your teamwork? Excellent, then invite others onto the product and help them too. Want to be a driver of good change in your team? Super, bring in Slack and you’ll build your reputation as an innovator who improves their organization. Others in your team will want to drive change too and you’ll pull them into your way of working quicker, more transparently, more autonomously.

Looking back on our landing page variants, can you see how we were already trying out some tactics to get customers over the Suck Hump? Some messaging to see what stuck and got a response? Yeah, me too. It’s experiments all the way down.

Who do want your customers to become?

Stewart had read an HBR article title Who do you want your customers to become? by Micheal Schrage. He’d passed the article on to me. I read it and we talked about it often, and its subtext was frequently felt in our decisions.

Stewart never said as much but it seemed like he was on his own self-guided course in marketing. Glitch had failed because it had not found a market. He’d felt the pain of laying people off and not succeeding. He didn’t need to touch the stove twice to know it could burn. He wanted to fix his failure by steeping himself in marketing and learning how to avoid it again.

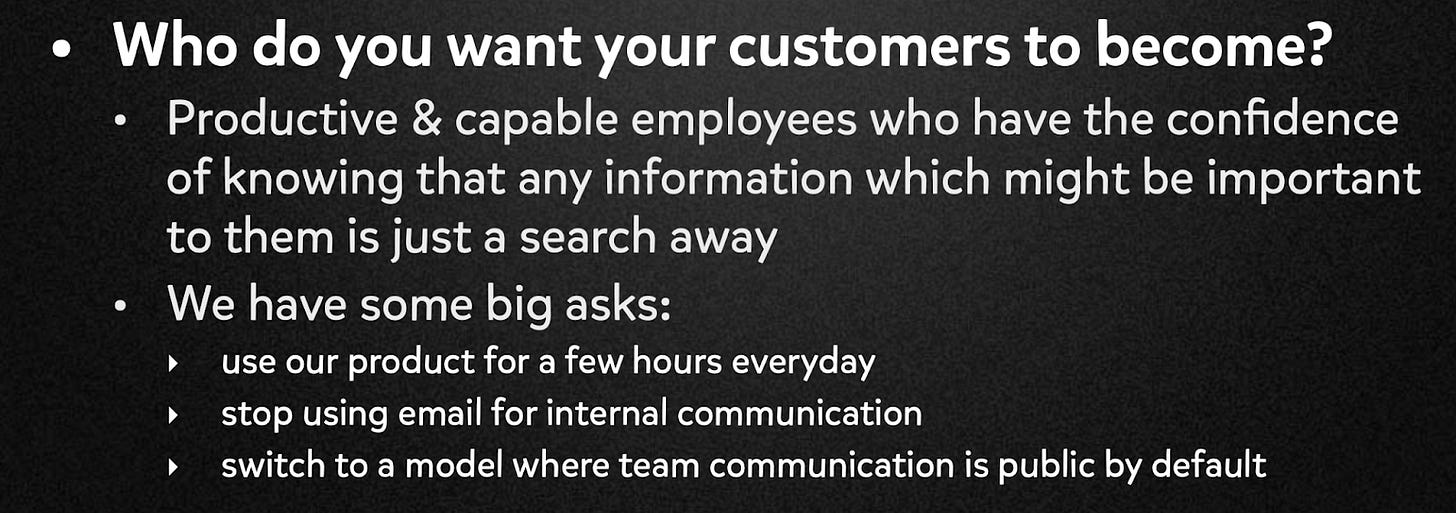

In a board meeting presentation Stewart shared with us, one bullet on the Positioning slide read:

We didn’t just want to launch a product with better chat. We wanted to help people be better versions of themselves at work, and to work with other people like them, in better teams and organizations.

If anyone had asked me before my Slack journey whether beliefs drove behaviours or behaviours drove beliefs, I would have answered that it didn’t really matter in marketing. It could be either.

But for a new product, I wanted to work on changing people’s behaviours, not their beliefs. To change their behaviours was easier and faster. I didn’t have to convince you a Big Mac is good for you or a smart choice. I just had to tell you about it when you’re hungry, and to have a restaurant nearby that can serve it to you quickly, reliably and cheaply. You can buy something whether you believe in it or not. Then once behaviours are changed, the human intolerance for cognitive dissonance acts to change beliefs. Maybe that Big Mac isn’t so bad in a pinch. At least, that was what I believed before Slack.

What we were proposing to do was the opposite: to change people’s beliefs so that they changed their behaviours. It was very risky. We needed them to believe a better way of working was possible to try our product. They already communicated, so what if they could communicate better? As Stewart put it, paraphrasing Who do you want your customers to become?

A central thesis is that all products are asking things of their customers: to do things in a certain way, to think of themselves in a certain way — and usually that means changing what one does or how one does it; it often means changing how one thinks of oneself.

We are asking a lot from our customers. We are asking them to spend hours a day in a new and unfamiliar application, to give up on years or even decades of experience using email for work communication (and abandon all kinds of ad hoc workflows that have developed around their use of email). We are asking them to switch to a model of communication which defaults to public; it is an almost impossibly large ask. Almost.

In short, we needed our customers to believe in a new, better way of working before they had even tried it. Or, at least to be open to trying a new, better way of working, with a hope that it would succeed.

Did I believe in this beliefs-before-behaviours marketing approach? Not at first, no. I argued against it, in theory. As I mentioned, my model for marketing before Slack was to work on behaviours and then beliefs.

But doing our landing page variants and talking with customers, I had seen how working on behaviours led to feature lists and functionality and, really, that game was over and small scale and not one we wanted to play.

To break through and really shoot for something that actually changed our customers, we had to start with their beliefs. They had to believe a better way of working was possible to get over the pain of the Suck Hump.

But what would help them believe?

That’s what we had to figure out. That’s what everyone at Slack had to figure out. As Stewart wrote:

None of the work we are doing to develop the product is an end in itself; it all must be squarely aimed at the larger purpose.

…

Ensuring that the pieces all come together is not someone else’s job. It is your job, no matter what your title is and no matter what role you play. The pursuit of that purpose should permeate everything we do.

And, as we ramped up to launch, that purpose loomed large. The moment of truth would arrive soon. We wrote it on the screen, on the whiteboard: August 14, 2013.

Launch day was coming very soon.

Up next: