Talking with customers

Mostly, listening. Hopefully, learning. Finding our frame. No one pays for chat. Earning a speaking role. What I heard you say.

In those really early days at Slack, in the summer and fall of 2013, I rode shotgun on a lot of customer calls led by Stewart. At first, I was puzzled: what was my job on the call? I wasn’t speaking.

So I listened and, because I had no other jobs, typed notes. A lucky habit of mine from university started to pay off — I could pretty quickly and accurately transcribe the conversation. That meant I could retain it and learn from it, which was my initial motivation for typing the notes.

The bonus outcome was that my notes now were no longer just for me. I could share them with the rest of the team in Slack and they could learn from them too. Each call became an opportunity to learn and share as a team.

Stewart would place his laptop between us at an angle on a desk and share the screen with me. I would prop my laptop on my thighs, listen, watch his screen, and type like mad. Skype was the cutting edge for calls at the time, and that was what we all used. (Slackbot even asked for your Skype name when you first used Slack.)

We talked with Hootsuite, who was a local Vancouver software success story. We talked with Rdio, who did streaming audio way before Spotify showed up. We talked with small product companies like Wantful and small consultancies like KNGFU. We talked with around 20 companies. Folks who worked at Slack had provided an entry to all of these companies through contacts or friendships.

These were the open doors we started to learn with. And we were lucky. The relationships we found on the other side of those doors were curious and welcoming. We were playing on easy mode.

Talking with these folks felt like shooting around ideas with peers. They too wanted us to succeed in our mission to build a product that helped them work better together. They wanted that product.

Asking for interviews

Independently, I took Stewart’s model of asking friends to use Slack and set up interviews with my own contacts and friends. I wanted to accelerate my own learning and he remained busy with businessman things.

Here was an example of my tantalizing pitch to a friend:

Hey (friend),

I've recently left Mobify and am working with a software startup called Tiny Speck on a new product. The Tiny Speck team were the folks who created Flickr. Now we're working on a new communication product for companies.

To understand what people need I'm doing some quick interviews. I'd like to interview you. It'll take about 10 minutes and doesn't require any preparation or follow up. Just get on the line with me and talk – Simple!

If you're interested, please take 1 minute and choose a time and date from below and we'll make it happen. If none of those options work for you, please suggest an option.

-- Wed, Jun 26 at 1:30 pm

-- Wed, Jun 26 at 2:30 pm

-- Thu, Jun 27 at 4:30 pmLook forward to talking soon!

Best,

James

(I’m going in to some detail and specificity here because I have had lots of conversations with folks facing the same challenge — how to get some initial users and feedback — and they have always wanted the granular details. I hope it remains fun and helpful to read.)

These calls with friends and contacts were all quick discovery / interview conversations. I scheduled 15 minutes or so with them and I had a list of 3 questions I wanted to cover sometime in the call.

How did you get started with your company? I wanted to learn about them, their role and their company. I’d adjust this question to their role slightly as needed, like, if they were a founder, What inspired you to start the company? But overall I just wanted them to get comfortable, to tell a story they likely knew pretty well, and to show them I cared about getting to know them.

How do you communicate today? This was totally open ended. Often the question met with some silence, like they had to consider it because it was so deeply assumed in their everyday, a kind of This is Water moment. “Email?” I sometimes had to prompt them.

If someone had never heard of Slack what would you tell them? As I’ve mentioned before, people sharing Slack needed to drive our product adoption so we might as well have an idea of what that word of mouth sounded like. Plus, it was incredibly valuable to hear how others described Slack. And it wasn’t pretty.

These conversations almost always ended up blowing past our time allocation because they wanted to keep talking, and I asked follow ups on these three questions. This proved to be both a good and bad sign. Good because it meant people were interested and we had some connection that mattered to them. Bad because it also meant we needed to often hone in on where our product was applicable to them.

I’ve mentioned before in our search for positioning, Slack didn’t fit into any of the existing software categories. So the conversations often had an element of, “Oh, it’s not that tool” to them as they got started. It wasn’t an email management tool. It wasn’t a project management tool. It didn’t really fit any existing category of software they already had and could compare it to. It wasn’t a better mousetrap, yet.

The folks I knew and interviewed were middle managers and directors and VPs, leading teams and managing people and being managed themselves. They were the middle of the organization and often decision makers for their teams.

If appropriate, the follow ups on my basic 3 questions sought to learn how applicable Slack could be for them. What did they want to use for communication? How satisfied were they with that set up? What made it work for them? What pains did they have? How had they tried to fix their situation before? Who’s job was it to address any pains? Did they care about communication? What could happen if they improved it?

I think a key to these conversations was that I wasn’t selling anything. I wasn’t doing demos — yet. I was interviewing — listening and probing on answers and making notes and leading with curiosity. I was trying to learn as much about our problem space as quickly as I could.

Finding our frame

I had some sense of the market Slack was angling towards because I had first-hand experience. The company I had left a few months earlier used a similar chat tool called Hipchat. Or, at lease a part of the company used it.

The total company was ~30 people when I started and ~75 when I left. It was a software development company selling e-commerce software for mobile devices. About half the employees were technologists – designers, engineers, project managers. Those folks used Hipchat all the time and used it pretty effectively.

On occasions, I joined them. But I was only a peripheral user. My main mode of communication in marketing, along with the sales team, the finance team, HR and the other leaders of the organization, was email. We had to communicate both internally and externally. HipChat only worked internally.

Communicating was drudgery enough in each of our days, like a tax on everything we did or discussed doing. Maintaining two modes of communication was too much of a pain to consider. If I wanted something, did I chat with someone or email them? Where did I go to find the answer to a question I had asked? To delegate a task? I know someone sent me a file, was it an email attachment or was it in Hipchat? Did I need another application on my computer to figure out?

The grandpa part of my brain was yelling: Get off my porch with your new tech, nerds!

In addition, I didn’t feel like Hipchat was for my kind of work. It didn’t seem serious or for capital-b Business. It seemed too casual, riddled with animated gifs and emoji and quick, flippant replies. It was where the young people in the company met up and goofed off out of sight of the adults, and maybe, eventually, got some work done. I resisted using it because I wanted to have my work considered as serious. Business.

And all the way back to my first Internet job in the late 1990s we had used mostly AOL IM for our office communication. But the leaders never did. All of us twenty-somethings who actually did the work (designers, developers, writers, project managers) used it all the time. But not the CEO. Not the GM.

So the dynamic of an organization living in two worlds felt familiar to me. I’d lived it from both sides.

And this perception that chat was for kids and not for leaders showed up consistently in my early interviews with folks. This was the framing we encountered, and the mental frame we’d have to contend with, going to market with Slack.

When I asked folks what they used for communication, email was always part of the answer. The first day when they started with the company, someone in IT had sent them their log in credentials and email address. Weren’t they all one and the same?

When I pushed them and asked if there was anything else they used, often there was Skype or MSN or another chat product like Hipchat or Campfire. But no one in the middle or top of the organization used those products. Their default was almost always email. That was how Business got done.

Messaging messaging

One of the decisions that these calls led to was in the specific language we used to describe Slack for our preview release and beyond. It may seem like a small thing, but I think it proved consequential.

We decided never to call Slack chat. Chat was for kids, like a toy. No one paid for chat. Slack was messaging and for teams. Chat was a consumer product. Slack was a business product. Chat was free. Slack was paid.

And for most folks, because they didn’t use chat for work, messaging didn’t really have any baggage attached to it. So Slack became very specifically and purposefully a messaging product. We never said chat.

Remember the MAYA principle from our sample landing pages chapter — Most Advanced Yet Acceptable? We used that tactic for our positioning and how we introduced Slack, and here we used it for our product framing as well.

Messaging was new and kind of different, though not too weird to be scary or strange. Did you ever send or receive a text? You’re already messaging.

Demos without safety harnesses

I remember one demo call Stewart and I did together that acted as a demarkation point in my work talking with customers. Before the call, I was doing interviews on my own. Stewart was doing demos with me riding shotgun.

The call was with Cal Poly, the research university. They were considering trying out Slack on a small team of about a dozen folks in their IT department. Perfect for our product at the time.

Stewart started the call doing introductions then moved ahead to do his demo. The demo he did was live in the Tiny Speck Slack workspace. No slides or dedicated demo instance of the product, sanitized and scripted for external presentation. Nope.

He just popped open Slack, shared his screen and away we went. He showed the live work in progress by the team: decisions happening, conversations about customers, revisions of files, updates from external software systems we used for code repositories or bug tracking, new signups in the #leads channel.

In the demo, he searched for conversations he wanted to reference and showed them, sometimes alongside unexpected ones that maybe shouldn’t have been included. He showed advanced search for only messages from him with the word fuck (from:stewart fuck) to show that the search did an advanced function called ‘stemming’ to return his mentions of fuck, fucking, fucker and so on. WTF said my internal business voice.

But by that time I knew this was his demo process. I’d been on the calls. I’d taken the notes.

Now zoom out with me from the call with Cal Poly to take a second and consider our approach.

At first it had felt a bit like a high wire act to demo our live work. It certainly gave me butterflies. But it also demonstrated in the simplest and most direct way the product in action. And it showcased Slack’s most valuable features (the most frequently used ones) exactly in the context that they were valuable.

And I’d say people really liked these demos because they were so vivid in showing what the product could do. It felt like there was next to zero artifice. We skipped right over the niceties of slides or introductions of a usual sales call and jumped straight into the product. Here is exactly how we work with our product. Here is exactly how we do our demos.

In response on those calls, people wondered aloud things like —

Did Slack integrate with product X? Yes, we said. Let us show you exactly how it does. And then we did. (Or no, we said. Here is how it works with a similar product. Let us add that new product you mentioned to our list.)

Could you have private conversations? Yes, we said. Let us show you. Here’s one now between James and Stewart negotiating our contract. (Oh goodness.)

Could you invite in external consultants and only give them a limited view of the information? Not yet, we said. But soon.

Does it work the same on mobile? Yes, we said. Let us share the laptop camera. (Stewart held up his phone to the camera.) Here’s my phone looking at the exact channel we were just in with the same content as on my laptop. I’ll post a message from my phone. “Balls,” it will say. Now let’s go back to the screen share on my laptop, and here’s the message.

We could answer pretty much any customer question just by showing them how it was already possible in Slack to do what they wanted. The “dogfooding” we were doing using Slack all day every day meant we had tons of experience with our own product. We found and fixed almost all the common problems quickly, and recognized and had plans for addressing future ones. The team at Slack were aces at making Slack work.

So by accident or by necessity, we managed to solve the biggest problem audiences have with demos: the leap of imagination to see how a product demoed in the abstract could work for them and their specifics. We just showed them how it worked for us, for our specifics. Again, it’s another example of how we worked to shrink the Suck Hump between our shiny, future, promised world and the work they did in their present. People responded well to this.

And let’s acknowledge too — part of the attraction to using Slack was the product being better, and part of the attraction of using Slack was buying in to a philosophy of working like Slack — nimbly, capably, autonomously. This was a pretty radical and attractive proposal for some folks.

Earning a speaking role

With important demos often we’d do a bit of scripting. I’d send Stewart a few messages in Slack at key times and he could show them coming in, getting a notification, replying to them, sharing a file.

It felt like a quick little two-hander play we came up with and mounted many times a week. It acted as my main live and customer-facing contribution to the demos.

Okay, now zoom back in with me to that Cal Poly demo I did with Stewart.

By that time, in my own interviews I’d been hearing customers’ perceptions of their communication pains, of what they might do differently, of what they needed. I felt like I had learned a ton and shared those lesson with the team through my notes. I’d even done some informal demos as a way to show friends how Slack worked.

But up until Cal Poly I’d been a mute note taker on the calls with Stewart, listening in the wings, and learning and scribing for teammates’ future and wider consumption.

Then the Cal Poly folks asked a new question. It was a question I’d been asked before, on my own demos, and I thought I’d answered it well. Stewart paused to consider the question. I spoke up with my answer. Whoa. I could see this was different and unexpected for Stewart. He let me finish my answer, then silently put up his hand like a stop sign.

The conversation shifted back to the Cal Poly folks and Stewart pointed his index finger at me, then put it up to his lips. Shh. Then he pointed at himself and mimed talking, like a duck eating a cracker. The message was clear: you stay quiet and take notes. I’ll do the talking. I felt my cheeks flush.

The call continued and finished reasonably well. Cal Poly were going to try Slack. I polished up my notes and shared them in Slack with the team. I didn’t bother to dwell on the small sting of my hurt feelings. The moment passed and we got on with things.

Then, a few days later, things changed for our demos. Stewart and I never talked about me jumping in on the call, and we had another demo scheduled. This time with MyPlanet, a team of 65 employees doing custom digital development work.

I was demo ready to go at the appointed time, assuming we’d run the same playbook as we’d been running. But when we hit the start time, Stewart was nowhere to be found. Gulp, I thought to myself, logged in and went for it.

That call turned out to be my first solo demo. Dozens then hundreds more demos followed over the months to come. Talking with customers became a big part of my job. I think if you asked any of my dozen or so teammates at the time, that’s what they would have said was my job.

Occasionally, Stewart jumped in on a few of the calls, and we reverted to how we’d done them, with him as the solo speaker. But that declined quickly as his attention turned to other items. I kept inviting him to the calls so he had some visibility. But he rarely attended.

Had I shown him I could do the calls? Did he just have more important businessman things to do? Could he not stand being on calls with me? Did I hurt his feelings jumping in? Could be any of those and other reasons. I never knew.

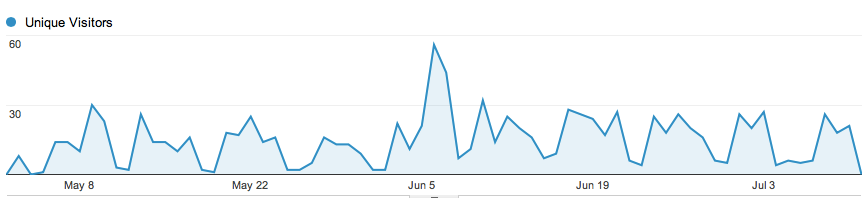

We had done our preview release to good results. We had over 16,000 people to invite to try Slack now! Around 500 more signed up every day. So I pushed ahead.

And since our customers could now get invited to try Slack, I shifted the demo process. I sent them an invite to set up Slack for themselves, and then I’d demo for them, in their new Slack workspace. I got them to invite me in to help set up, get their preferences right, show them what they could do and answer their questions. I hung around and shared tips and tricks. Essentially, I guided a live product tour.

Two or three demo calls per day ended up being the most I could reasonably do. I spoke with OKCupid, Ayogo, OpenSky, Twitter, Webscale, Accenture, Planned Parenthood, Galen Healthcare and more. All of them at the time were small, cutting edge technology companies, or small technology teams within larger organizations. Pretty much all proved to be open doors for us to push on.

Some were new to Slack. Some were already using Slack in fledgling ways. Some were trying to use Slack and not quite getting it, or getting it in a small group and trying to convince more people at their organization to use Slack. Helping these folks find out if Slack could work for them felt like valuable and rewarding work, so I kept doing it. We’d found a very receptive market for our product and a fun way to help them get it.

Finding a groove

The more demo calls I did, the more I saw some general patterns begin to emerge. I kept up my note taking as well as I could while still running the demo, still sharing those notes back to the team.

But the notes grew sparser and started to only highlight the differences in calls rather than repeating the commonalities, because there were more commonalities all the time.

It started to gradually feel very much like one of those moments in sports where players say the game slowed down for them and they could clearly see the next play coming. The calls slowed down for me and I could pretty clearly see the direction our conversation was headed.

I couldn’t just jump ahead because the person on the other end of the call had to get through their thinking on their own, at their own speed. But the pattern of how the conversation was going started to shape into a predictable, repeated groove.

I knew Stewart was still lightly paying attention to the calls, because he commented on the notes or mentioned something in passing from one of the customers I’d met with. But it felt like his absence on the calls was a vote of confidence for me. It felt too like we were humming along and making progress, our confidence building. This Slack thing might have some legs to it!

The same way I had started to build a shared topography with Stewart about how we wanted to take Slack to market, our team started to build a shared topography about our customers’ contexts and our product’s problem space.

And the information flow worked bi-directionally. I started to absorb feedback and input back from the team that I added to my calls. I picked up and riffed on something JR said in the office one day: Slack is a terrible single-player experience. To use it well, you needed to use it with ~4+ people and for more than 3 days. The prescriptive specifics proved beneficial because no one (including us) actually knew how to meaningfully trial Slack at the beginning.

And, like any first date, it proved incredibly important how people started. Most people encountered Slack for the first time from a teammate. Each successful instance of the product at a company had a lead person who took it upon themselves to change the way their team worked together. Sometimes this was their job, like with an IT manager. Other times it was an interest or passion project.

In pretty much every case, it was what this lead person said about Slack that mattered most in how Slack got introduced to most people. They acted as Slack’s messenger.

In my calls with people this same pattern recurred: someone needed to be fed up with the way a team was communicating, then try to find a better way to lead the change. This didn’t have to happen all at once. The frustration could be simmering for years without an outlet. Many false starts could have preceded a team trying Slack.

The notes from calls started to clarify how people described Slack and introduced it to their teams. We started to see that this peer-introduction pattern drove our product adoption.

Our best marketing proved to be from word of mouth as people talked with their peers and teammates about Slack. It didn’t mean we had no role to play. But our role was much more guiding than telling. We needed to prompt our customers in the best possible way to set the stage for a favourable impressions of Slack.

And we also needed to capture the best word of mouth for our own marketing to scale it and make it as credible as possible.

What I heard you say

From the notes of my calls, I also started sending snippets to the folks I had spoken with on the customer side.

This started to take on a fairly standard format. I’d repeat and validate their words, looping what they said back to them to confirm my understanding. It was simple and fun. What I heard them say on the call was (insert their words, perhaps with some very light tidying). Did I have that right? If so, here are the follow up action items for us to do and track.

I used the ‘What I heard you say’ tactic to move customers ahead in their Slack adoption (or not), and so they could build their internal momentum to use Slack (or not). I also used the ‘What I heard you say’ tactic to start to build our external marketing.

To Gino Zahnd, the CEO of startup Cozy, I wrote ‘what I heard you say is, “The biggest thing is nobody thinks about Slack – it just always works. The tool itself gets out of our way so we can get work done. Any good tool makes it so you don’t think about the tool but the things you want to get done. I never think about it – that’s perfect.” I asked Gino, have I got that right? And if so, is that something we could use to help new teams understand Slack when we launch more widely?

Yes, he said. And we launched with his quote on the home page.

We did this for all our quotes. A dozen simple testimonials from our early users got created by listening, writing their words and asking for their permission to share what they’d already said. Saying, ‘What I heard you say…’ felt like a magic trick that always worked. I’m almost a bit reticent to share it in writing here because it worked so well and, if it suddenly gets overused or abused, will stop working.

Did we ever share a customer’s words back in a smoother or clearer way than they had spoken them? Yes. Did we also make them sound smart and eloquent and credible? Also, yes.

I don’t remember ever getting a negative response back from the ‘What I heard you say’ approach. Understanding how important the word of mouth introduction was proving to be, we built up our customer’s testimonials before we ever needed them. Reflecting back someone’s words to them showed them how we valued their input and handed them back their own story of success in a formalized way for repetition.

In short, through talking with customers and really listening to them, we came to an understanding that our customers’ words would have a huge effect on our marketing, and whether our business actually survived.

Up next: You put your name on every job you do

Starting to think about Slack culture through stories. Codifying values in stories. $20 to stack a cord of wood. Painting the back of the drawer.

Thank you for reading this far! If you liked this post, please share, save or like it.