#zork

How a classic text-based game informed how we built Slack. The single-player experience sucked. Work as role-playing game. From Zork to Slackbot.

A very distinct line divided digital people in general as well as all of us at Slack: growing up, did you play Zork or not?

First released in 1977, Zork is a text-based adventure game. The object of the game is to explore the ruins of an underground kingdom. All in text. The game straddles a gap between computer video games and Dungeons and Dragons-style tabletop role-playing games. To fans, it’s awesome.

When someone at Slack referred to Zork, it felt very much like a test of your credibility as a true, long-committed computer geek of a certain age. If you’d played Zork, you earned some geek cred. It was sort of a secret in plain sight, with inside jokes about being eaten by grues that flew over your head if you hadn’t played.

And it wasn’t easy to play Zork, especially compared to later console or online video games. You had to figure out how to play, almost entirely on your own, in the game. No speed runs, no walkthroughs or player videos on YouTube. Minimal manuals.

But it was rewarding in ways that revealed themselves through the game play. It was hard fun, the best kind of fun. And because it was all text, it felt much more like reading an interactive story, that surprised you at each interaction, rather than playing through staged scenes where controller dexterity and finger reactions mattered. You could take your time with Zork and let the game unfold. It was no problem to leave your character and then come back to the game later. Zork waited.

Maybe this is hard to imagine for folks unless you’ve played? Maybe it’s hard to see why it might have been compelling, like it’s hard to watch movies before the talkies?

Probably. So here’s an example of Zork game play. As a player, imagine your beige computer, big CRT monitor perched on its hardware box, disc slots with their meh mouths facing you, green blinking text on the black screen.

You start Zork with this text prompt:

West of House

You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door.

There is a small mailbox here.

That’s it. That’s the whole intro. You read that text and are presented with a blinking > prompt, waiting for your instructions. Again, that’s it.

No graphics. No hints. No help. No tips. The constraint in the game felt compelling and frustrating at once. Something is expected. What? I don’t get it. Maybe I get it? I guess I’ll type something and see what happens!

If you were pimply teen lucky enough to have a friend who had played Zork, or a book on the game, you might have some hints to get you started. Most importantly, you might have a list of commands that worked on the blinking > prompt. Maybe even some context for the larger story.

Today it takes less than 10 seconds on the web to find a list of Zork commands. Verbs like Look, Get, Take, Drop, Attack all work well. Through the web we all have access to the double-edged sword of everything all the time. But when Zork came out, and when I first played it, all of the game had to be discovered through the game.

That first time I played Zork, I monkeyed around for a few hours, found a few commands that worked, got eaten by a grue, restarted, got eaten, and went outside to ride bikes. It was too hard. None of my friends played. If I’d had friends that played, I might have persisted because there was someone to help and impress and someone who could help me and impress me.

But I didn’t have anyone else. Instead of making much progress in the game, I got a lot of this kind of thing.

Adventurer: what is happening?

Computer: THAT SENTENCE ISN’T ONE I RECOGNIZE

And I failed to learn the commands I could use.

Adventurer: go to house

Computer: YOU CAN’T GO THAT WAY

Zork gave me the same response when I told it to go to hell, so maybe I needed a longer attention span at the time, or different friends. In any case, I had played but never played for long or gotten very far.

Playing Zork at Slack

Anyway, this is a long way of telling you that one of the early things we did at Slack is launch and play Zork in Slack.

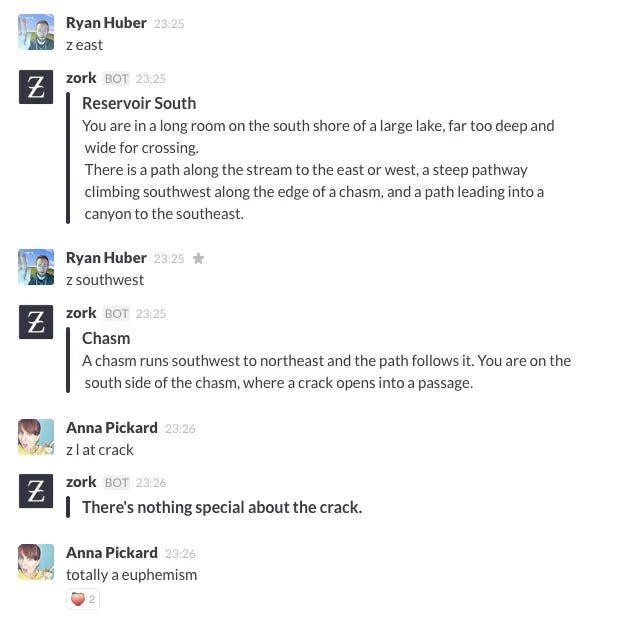

One of our developers, Tim Lefler, created #zork. In that channel lived the full text-based game, or so it seemed. The actual game lived on an outside server Tim ran and the Slack integration with that server acted as a proof of concept for later integrations he was building. But for the purposes of us Adventurers, Zork live in Slack.

One day Tim set up Zork and invited a few folks to play. Except we didn’t play as an individual Adventurer. James didn’t play as James. Tim didn’t play as Tim. All Slack employees in the channel played as the same player: Adventurer.

Each day folks would play a few turns of the game in #zork. Everyone else at Slack would get a chance to watch, cheer on the player, make suggestions, and, if feeling up for it, take over the Adventurer. There was an element of self organization to our play, as we took turns and demonstrated trust in each other.

Our common asset was the Adventurer and the game and the adventure we were sharing. We could all play and all our play was public in front of our teammates. Choose to pick up the command prompt and play a few turns? You felt a little light pressure to not arse things up in front of your teammates.

Writing about playing Zork in Slack now makes it sound like a goofy thing for well-paid professionals to be doing with their precious time together. Remember, we were still a $0 revenue startup burning through our reserves of cash. Survival remained unlikely, even if we had done well with our preview release announcement.

But it was really fun to play Zork and in many ways a really effective team building exercise. It also taught us some lessons that we went on to use in Slack.

But all the messages in #zork were time stamped. So no one spent too much time playing because if you did you were essential demonstrating your goofing off to your teammates.

But taking a break, in 5 or 10 minutes, you could catch up on how the Adventurer was doing and contribute to some progress. Or get eaten by a grue.

Playing work with Slackbot

Playing Zork collaboratively highlighted for us a few lessons. It showed or reinforced how much fun work could be. It also made clear to us that work itself was kind of a role playing game, especially when work was done mostly through computers, and through text.

In trying to convince people to try out our new product, and competing in a world of blueniform clothes and boring products, having a culture that was a bit goofy, that prized having fun and playing games with skill, seemed like it could be a competitive advantage. People responded well to it. It was hard to be against fun.

And it did turn out to be one of our competitive advantages. Everyone at Slack seemed very good at their job and very good at playing games, especially games of words and stories, and so very good at playing the game of work.

Whether explicitly or implicitly, we understood how games joined us together and created a common social language that spawned other conversations, or didn’t. Just like work, the game became a thing we did together in pursuit of a common goal.

I started to also notice that the spirit and sensibility of games and play really informed how we worked at Slack, how we built Slack. It informed how we wanted to engage with our customers and even how we wanted our customers to use Slack.

So let’s go back to the start of this post and the description of Zork as a “text-based adventure game.” Add that to our emerging understanding that work is a game. And layer into it the understanding that we had to get over the Suck Hump of starting from scratch.

Then consider how we launched Slack and understood that it stunk (as I’ve mentioned many times before) as a single-player experience.

Shake all those ingredients together and what do you get? A recipe for Slackbot.

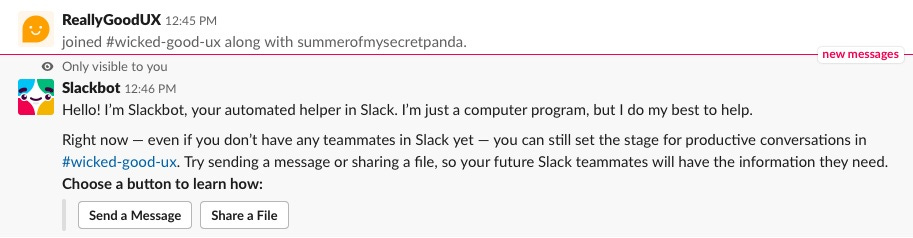

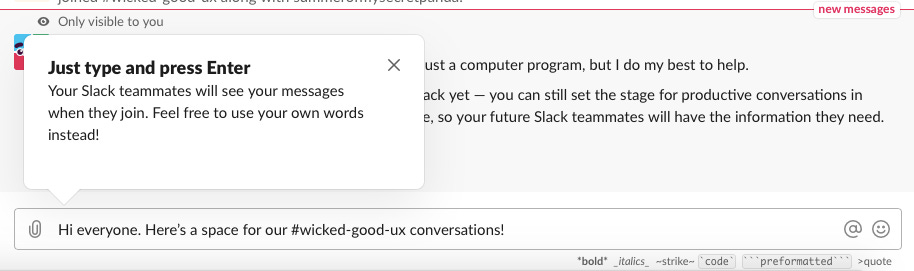

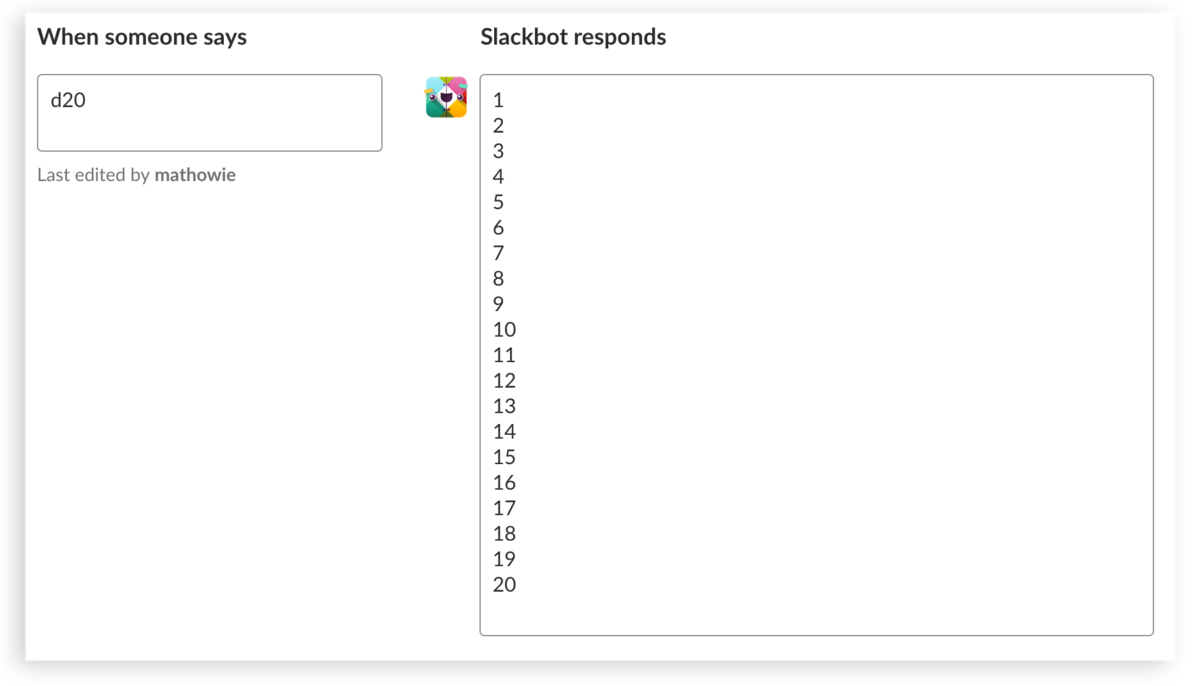

Slackbot was a big part of our answer to smoothing the Suck Hump and getting people started on Slack. We took the model of a text-based adventure game, added some graphics, made the commands obvious, and applied it to Slack. Learning how to play Slack became easiest to do by playing Slack.

Here are some examples of that in action, led by our character in the game, Slackbot.

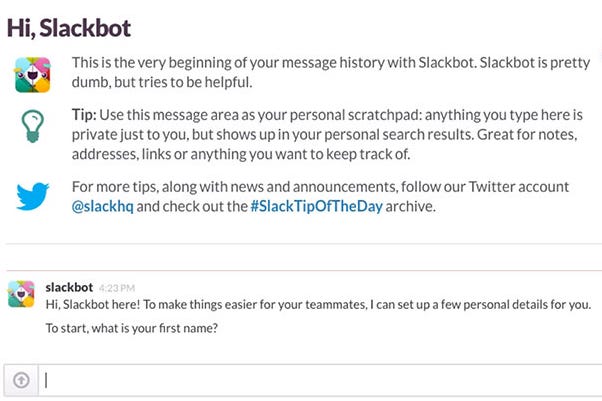

Need people to break the ice of the cold start problem with this weird new application and teach people what they can do with it? Yes, Slackbot can welcome them.

Need to start people interacting with the main function of the application — messaging? Yes, Slackbot is your friend.

Need people to add in their first and last name so teammates recognize them? Slackbot can do that in a quick conversation.

Slackbot acted as teacher, guide, host and helper all in one. It was the key part of our onboarding process for new users, their first experience with Slack. It nudged folks in good directions. It gave our product a voice and tone and did the next hardest thing we needed done — starting a conversation in a product designing for conversations.

Then once you got used to Slackbot you could extend what it could do, personalizing it for your own purposes as an assistant.

Tracing the line back from Slack to Zork is easy and it worked. Once you see it, I believe you can’t unsee it. Work is a role-playing game and Slack is a new kind of Zork. I hope you don’t get eaten by a grue.

Up next:

Talking with customers

In those really early days at Slack, in the summer and fall of 2013, I rode shotgun on a lot of customer calls led by Stewart. At first, I was puzzled: what was my job on the call? I wasn’t speaking.

This has been my favorite post thus far. I laughed out loud on the giving up on Zork and riding bikes. I didn’t play Zork but had the same experience with another game growing up. Grappling with this new technology with minimal instructions taught our generation a lot. And having that shared experience and language among co-workers so useful. But more than that - powerful. Bringing metaphor into work, giving it a deeper (and much more fun) layer can be where the real shift happens.